Dislocation of the radial head can be congenital, related to underlying disease, or traumatic. In the emergency department (ED), most patients with acute radial head dislocations are men who have sustained a high-force injury.

These dislocations typically are due to external rotational stress on the ulna.2 Forearm fractures and dislocations, especially in children, are often misjudged, and it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for these injuries in patients presenting after elbow and arm trauma.

In children, the radial head is much more commonly subluxated than it is dislocated. See Reduction of Radial Head Subluxation.

Background

Isolated radial head dislocations are exceedingly rare.4 Some argue that they do not even exist and believe that radial head dislocations occur only with disruption of the ulna, including “plastic deformation” (described as Monteggia equivalents in children; see below).5 More commonly, radial head dislocations are complicated by complete elbow dislocations or fractures, as in the Monteggia complex (see below).

Radial head dislocations may be seen in association with the rare isolated interosseous membrane injury of the forearm or in association with an Essex-Lopresti injury (fracture of the radial head with concomitant dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint and disruption of the interosseous membrane).6, 7 Radial head dislocations have also been rarely seen with associated humeral condyle fracture.8

The radial head can be congenitally dislocated in isolation or in conjunction with other congenital abnormalities, such as those in Steel syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, nail-patella syndrome (hereditary onycho-osteodysplasia), autosomal dominant omodysplasia, multiple hereditary exostosis, multiple cartilaginous exostosis, mesomelic dysplasias, radioulnar synostosis, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteochondromas, and achondroplasia.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Radial head dislocations have also arisen from complications of osteomyelitis, osteochondromatosis, brachial plexus birth palsy, and arteriovenous malformations that cause osteolysis.

Traumatic radial head dislocations are most often seen with associated fractures. Monteggia clinically noted and described the combination of radial head dislocation and proximal ulnar fracture in 1814, before formal radiography was available.25 More than a century later, Bado26, 27 further classified the Monteggia injury into four types on the basis of the angulation of the fracture and the direction of dislocation.28, 29

The Bado classification (see Table 1 below) is useful descriptively but not prognostically. “Monteggia equivalents” are occasionally seen in children and involve dislocations of the radial head with plastic bowing of the ulna.30

Table 1. Bado Classification of Monteggia Injuries (Open Table in a new window)

| Classification | Incidence | Description |

| Type I | 60% | Fracture of the proximal or middle third of the ulna with anterior angulation and anterior dislocation of the radial head |

| Type II | 15% | Fracture of the proximal or middle third of the ulna with posterior angulation and posterior dislocation of the radial head |

| Type III | 20% | Fracture of the ulnar metaphysis distal to the coronoid process with lateral dislocation of the radial head |

| Type IV | 5% | Fracture of the proximal or middle third of the ulna and fracture of the proximal third of the radius with anterior dislocation of the radial head |

Monteggia fractures may occur with other fractures (eg, Galeazzi) or other dislocations (eg, transolecranon fracture-dislocations).25 Radial head dislocation is often associated with significant trauma (eg, motor vehicle accidents, pedestrian–motor vehicle accidents, or significant falls). The proposed mechanism is force directed onto an outstretched, pronated arm.31 Other mechanisms of injury, such as hyperextension of the elbow with the forearm in midprone position, have been reported.4

Indications

Radial head dislocations are easily missed on radiographs and require a high index of suspicion for diagnosis.32, 33, 5 Undiagnosed chronic radial dislocations lead to poor outcome, limited function, and chronic pain.34 The therapeutic goals are as follows35 :

-

To maximize patient comfort

- To recognize and treat any coexisting injury

- To reduce the radial head dislocation within 6-8 hours of injury

Diagnosis

Physical examination

A person with a radial head dislocation typically holds his or her elbow flexed at 90º and resists passive and active range of motion (ROM) at the elbow, including pronation and supination. The elbow is often swollen and diffusely tender with increased point tenderness over the radial head (see the image below). In the case of Monteggia fracture, crepitus may be present over the proximal ulna. The radial head may be palpable in an anterolateral or posterolateral location, and the forearm may appear shortened and angulated.

Swollen elbow from radial head dislocation.

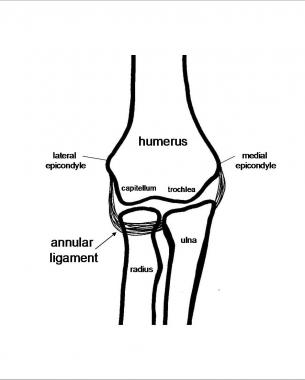

In patients with suspected injury, standard anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique radiographs should be taken of the elbow and forearm (see the images below).11 (See Elbow, Fractures and Dislocations – Adult.) A clinician should evaluate the radiocapitellar, ulnohumeral, and radioulnar joints, as well as the entire radius and ulna, for evidence of dislocations or fractures.25 Consideration should be given to imaging the joint above and below for assessment of possible additional injury as needed.

Landmarks on lateral elbow radiograph: radial head (R), ulna (U), capitellum (C), and humerus (H).

The radiocapitellar line can be used to evaluate for subluxations and dislocations of the radial head.36 This line, drawn through the middle of the neck of the radius, normally bisects the capitellum in any degree of flexion or extension (see the image below).37 Deviation of this line suggests capitellar or radial dislocation.

Normal radiocapitellar line drawn down through middle of neck of radius should intersect capitellum.

Be sure to carefully evaluate the ulna for any fracture or plastic bowing deformity suggestive of a Monteggia complex or equivalent.38 In a Monteggia fracture, the apex of the ulnar fracture points in the direction of the radial head dislocation (see the image below).

Abnormal radiocapitellar line due to dislocation of radial head. Line does not bisect capitellum. Apex of ulnar fracture points in direction of radial head dislocation (anteriorly, in this case).

A novel assessment technique referred to as the ulnar bow sign can be used to assess for plastic ulnar deformities that may be found in radial head dislocations.39 This requires a true lateral radiograph of the ulna; the bowing might be missed on a lateral radiograph of the elbow.11, 5 (See the image below.)

Abnormal maximum ulnar bow is present when maximum perpendicular distance (red arrow) drawn from the dorsal ulnar border (dashed line) exceeds 1 mm.

In certain cases where the injury remains in question, computed tomography (CT), three-dimensional (3D) CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be indicated for further evaluation.2, 40

Once the dislocation is recognized, the direction of the radial head displacement (ie, anterior, posterior, or lateral) must next be noted.41 A reduction must be performed to restore elbow function with flexion, pronation, and supination.41

Contraindications

The management of a radial head dislocation is dictated by the presence or absence of an associated fracture. If an associated fracture is present, the forearm is not considered stable; in such a case, bedside reduction of a radial head dislocation typically is not appropriate.

Whereas a conservative approach may be considered in children with Monteggia injuries, operative repair is typically recommended for adults.42, 43, 44 In deciding on the managment approach, the type of ulnar fracture is more important than the direction of radial head dislocation.25 Adolescents seem to have the best prognosis for Monteggia fractures.25

Open and complex radial head dislocations, as well as Monteggia fractures in adults, necessitate consultation with an orthopedic or hand surgeon.45 Such injuries are usually reduced with fixation in the operating room.46, 47, 48

Periprocedural Care

Equipment

Splinting supplies are needed following reduction. If procedural sedation is used, the standard monitoring equipment is necessary.

Patient Preparation

Anesthesia

Reduction is optimally performed on a relaxed and comfortable patient by using one of the following methods:

-

Instillation of a local anesthetic into the joint

- Procedural sedation

- General anesthesia

Positioning

For most reduction techniques, the patient may sit upright or lie supine. Bado suggested that reduction be performed in the opposite direction from the direction of the external force at the time of injury and that the forearm be immobilized in this position.27

Most injuries occur in a pronated position; therefore, after reduction, splint the forearm in the supinated position with 90° elbow flexion.

Technique

Approach Considerations

Assess and document the neurologic and vascular status of the arm. Further evaluate the arm on the basis of the type of injury (see below).

Monteggia injuries were once treated nonoperatively in adults. However, surgical treatment of these injuries results in decreased pain, less restricted motion, decreased valgus, and less late neuropathy.49, 50, 51, 52, 53 Once the ulna is fixed, often by means of operative compression plating,54, 55 the radial head often self-reduces. If orthopedic or surgical care is not immediately available, the practitioner who provides initial treatment may splint the fracture and perform reduction as instructed below, with prompt referral to a specialist.

Although operative repair is recommended in adults, a conservative approach is often used in children with Monteggia injuries.42, 43, 56 Children may be treated by means of closed reduction of both bones and immobilization in a long arm cast.57 It is important to consider the Monteggia equivalent injury associated with plastic bowing of the ulna; the radial head might continue to redislocate with pronation after reduction.30 The key to reduction in children is to obtain normal length and alignment of the ulna, after which the radial head typically falls into place. When necessary, open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) is performed.58

Some advocate primary operative care in complete ulnar fractures because of the shortening and angulation that may occur without fixation. In general, surgical repair of ulnar fractures in children may involve relatively smaller plates and screws than those used in adults because of rapid osseous repair. In transverse and short oblique fractures, an intramedullary wire may be used.

Pearls

Be wary of other serious associated injuries, especially to the head and chest.

Carefully evaluate the bones and joints above and below the injury.

Always assess and document the neurologic and vascular status of the arm both before and after reduction.

Before discharging a patient with a forearm or elbow injury, always use the radiocapitellar line to check any misalignment of the radial head.59 This is especially important in the case of an ulnar fracture.

Delayed treatment

Many radial head dislocations are missed on initial presentation and may not be diagnosed until years later.60 Previously undiagnosed radial head dislocations are fixed operatively in adults and are usually fixed operatively in children.61, 62 After 3 years of dislocation, deformities develop in the radial head (dome-shape deformity) and the radial notch of the ulna.63

A retrospective review showed a high success rate with surgical management of chronic posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children.64

The triceps tendon can be used to reconstruct the annular ligament through techniques described by Bell Tawse,65, 66 Lloyd-Roberts, and Bucknill.67 DeBoeck described a procedure without annular ligament reconstruction.68

In some cases, the nonreducible radial head may have to be excised.69 Seel, Peterson, and Papandera have also described alternative reduction techniques.

Reduction of Monteggia Injury

Type I (anterior dislocation)

Closed reduction

Nonsurgical treatment may be considered in children.70 The key to success is proper reduction of the ulnar fracture. Reestablish the proper length of the ulna, and correct any angulation. Once the ulna is reduced, the radial head is easily replaced. With the elbow flexed 115° to relax the biceps, provide longitudinal traction and fully supinate the arm while applying posterior manual pressure to the proximal radius anteriorly. Splint the arm in 90° flexion and supination, using three-point molding to counteract the forearm musculature.

Confirm reduction with radiographs. Repeat radiographs in 1 week to assess continued proper reduction. A long-arm cast may be used for 3 weeks, followed by 3 weeks in a short-arm cast.

Open reduction

Open reduction is indicated in cases of failure to maintain ulnar or radial anatomic position. Ulnar osteotomy with elongation and reduction of the angulation is performed along with open reduction of the radial head.71

Type II (posterior dislocation)

Closed reduction

Reduction is accomplished with longitudinal traction with the elbow in extension because the ulna is most stable with the arm extended. The radial head is reduced with pressure directed anteriorly onto the radial head. Once reduction has been accomplished, three-point cast molding is placed with the elbow in extension and pronation (70° of flexion).

This metaphyseal fracture heals quickly, and the cast can usually be removed in 3 weeks. However, immobilization must continue until union of the ulna occurs, which may take as long as 10 weeks in older patients. Flexion may return slowly.

Open reduction

Operative indications are the same as those for type I Monteggia injuries.

Type III (lateral dislocation)

Closed reduction

The incidence of posterior interosseous nerve injury is high with this lesion72 ; however, such injury typically resolves spontaneously and rapidly. Reduction is accomplished by hyperextension and stabilization of the olecranon followed by a valgus force to the olecranon. This force corrects the greenstick fracture, and the radial head often spontaneously reduces. If necessary, direct medial pressure to the radial head facilitates reduction.

Controversy exists concerning the best type of immobilization for a type III injury. Some advocate splinting, as in type I Monteggia injuries (115° of flexion), and some recommend immobilization in a long arm cast in extension with valgus stress applied to the ulna.73 The cast should be maintained for 4-6 weeks.

Open reduction

This type of injury is most commonly irreducible because of annular ligament interposition.

Type IV (fracture of both forearm bones)

Closed reduction

Nonoperative methods for this unstable fracture are difficult and often unsuccessful.

Open reduction

Unlike the other three types of Monteggia injury, type IV lesions usually necessitate initial surgical stabilization of the radius and ulna fractures. The elbow is immobilized in supination and hyperflexion (115°) in a long arm cast for 3 weeks. A short arm cast is applied for an additional 3-4 weeks.

Reduction of Isolated Radial Head Dislocation

Anterior

Supinate the arm, and flex the elbow to 115° to relax the biceps. An assistant holds the humerus distally for stabilization while the practitioner applies distal traction to the wrist and direct posterior pressure to the radial head.74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79 (See the video below.)

Technique for reduction of anterior radial head dislocation.

Posterior

The arm is held supinated in extension at the patient’s side, and the humerus is stabilized distally.80 With care taken not to hyperextend the arm, distal traction is placed at the wrist, and anterior pressure is applied to the radial head. (See the video below.)

Technique for reduction of posterior radial head dislocation.

Lateral

As with the technique used in a posterior reduction, provide stabilization to the distal humerus and place distal traction at the wrist while applying medial pressure to the radial head. (See the video below.)

Technique for reduction of lateral radial head dislocation.

Failure to reduce

In some instances, the elbow is not reducible with closed reduction techniques, and operative repair is necessary. Possible reasons for this include delayed treatment,81 presence of interposed tissues that impede reduction, “button holing” of the radial head through the joint capsule, and an extremely unstable elbow.82 In rare cases, osteosynthesis or resection of the radial head may be necessary.

Reduction of Chronic Radial Head Dislocation

Chronic dislocation of the radial head is rare and often goes undiagnosed. These dislocations may be of either congenital or traumatic origin.83 Although they might be initially asymptomatic, arthritic changes may restrict movement as time goes on.84 Long-term dislocations often result in valgus deformity of the elbow, which may subsequently give rise to ulnar and interosseous nerve disturbance.83 Furthermore, when the radial head is left dislocated for an extended period, anatomic changes begin to occur to the radial head and the radial notch of the ulna.63

Treatment of chronic radial head dislocation is controversial, ranging from neglect to ORIF. Three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) and 3D-printed bone models have proved useful in the approach to surgical correction.40

Closed reduction is based on the direction of dislocation, as outlined above.

Surgical intervention is recommended to restore function, relieve pain, and improve cosmetic appearance.83 Open repair of the ulna is carried out if necessary. For the chronically dislocated radius, two surgical options are available: resect or preserve the radial head.

Advocates of radial head–sparing reconstructions have touted the advantages of fewer complications and substantial pain relief; however, improvement of range of motion (ROM) is limited, and additional surgery is needed 25% of the time.83, 85 Radial head–sparing techniques include reconstruction and reattachment of the annular ligament and osteotomy of the radius or ulna.83, 86, 87

Postprocedural Care

Once reduction is complete, reassess and document the neurologic and vascular status of the arm. Evaluate the elbow in its full ROM (varus, valgus, pronation, supination) and check for soft tissue, bony blocks, or other instability. Apply a posterior splint in 90° flexion, and supinate for isolated dislocations.

Obtain postreduction radiographs, and reevaluate the radiocapitellar line. If reduction is performed in the operating room, the stability of the radial head may be checked with fluoroscopy. Patients are generally admitted for 24 hours to observe for possible complications (eg, compartment syndrome).

The ROM exercises can be initiated when pain and swelling permit. Frequent radiographs should be taken to confirm that the elbow remains reduced during early rehabilitation. In isolated radial head dislocations, ROM is instituted within a few days, and the splint is generally discontinued after 1-2 weeks if the elbow is deemed stable. Unstable elbows require longer immobilization.

After such an injury, a loss of 5-10° of extension in comparison with the contralateral elbow can be expected; however, uncomplicated radial head dislocations have a favorable prognosis.88

Follow-up with an orthopedist is mandatory.

Complications

Complications include the following:

- Osteomyelitis – Carefully evaluate for signs of an open fracture and treat appropriately to avoid serious infection 89

- Compartment syndrome – Elevated compartment pressures are not uncommon after serious forearm injuries; for this reason, hospital admission for observation is advocated

- Neurologic injury – Although this is uncommon, it may occur as a consequence of the injury or as a result of the reduction 90, 91 ; the posterior interosseous nerve is the most commonly injured nerve, with injury resulting in weakness of finger or thumb extension 92, 93, 94, 95, 96 ; sensory involvement is rare; postreduction neurapraxia is often a temporary problem that resolves spontaneously 97 ; paralysis that does not improve may necessitate further surgery; ulnar nerve compression may occur as result of the radial head dislocation 6

- Chronic pain – Long-term disability and chronic pain can result from missed radial head dislocations, which occur in as many as 50% of cases

- Redislocation – Immobilization does not guarantee the maintenance of reduction; even if immobilized, the radial head may spontaneously dislocate; repeat radiographs should be obtained at follow-up 98 ; redislocation is especially common with the Monteggia equivalent injury seen in children 30

- Loss of motion – Reduced ability to pronate and supinate or flex and extend the elbow is common immediately after cast removal; if loss of motion is promptly treated, function usually returns completely within 3 months 99 ; stiffness may be avoided with early ROM exercises or surgical capsulectomies 100

- Periarticular ossification – Periarticular ossification can occur in cases of chronic dislocations but tends to reabsorb after reduction; heterotopic ossification should be excised more than 6 months after injury or treated with indomethacin or radiation

- Posttraumatic proximal radioulnar synostosis – This complication occurs in a minority of injuries and may be treated with anti-inflammatory medications, radiation, or surgery 101, 102

- Nonunion of fracture

- Osteochondritis dissecans – This can occur in chronic and recurrent dislocations and subluxtions of the radial head 103

- Osteonecrosis 100

References

- Ovesen O, Brok KE, Arreskov J, Bellstrom T. Monteggia lesions in children and adults: an analysis of etiology and long-term results of treatment. Orthopedics. 1990 May. 13(5):529-34. Medline.

- Kim E, Moritomo H, Murase T, Masatomi T, Miyake J, Sugamoto K. Three-dimensional analysis of acute plastic bowing deformity of ulna in radial head dislocation or radial shaft fracture using a computerized simulation system. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012 Dec. 21 (12):1644-50. Medline.

- Wang J, Chen M, Du J. Type III Monteggia fracture with posterior interosseous nerve injury in a child: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Mar. 96 (11):e6377. Medline.

- Rethnam U, Yesupalan RS, Bastawrous SS. Isolated radial head dislocation, a rare and easily missed injury in the presence of major distracting injuries: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007 Jun 29. 1:38. Medline. Full Text.

- Lincoln TL, Mubarak SJ. “Isolated” traumatic radial-head dislocation. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994 Jul-Aug. 14(4):454-7. Medline.

- Singh AP, Dhammi IK, Jain AK. Neglected reverse Essex-Lopresti injury with ulnar nerve compression. Chin J Traumatol. 2011 Apr 1. 14 (2):111-3. Medline.

One thing I’d prefer to say is the fact that car insurance canceling is a feared experience and if you’re doing the proper things being a driver you simply will not get one. A lot of people do obtain the notice that they have been officially dumped by their own insurance company they have to fight to get further insurance after a cancellation. Low-cost auto insurance rates tend to be hard to get after the cancellation. Having the main reasons with regard to auto insurance cancellation can help owners prevent losing one of the most vital privileges offered. Thanks for the strategies shared by means of your blog.

There are definitely plenty of particulars like that to take into consideration. That may be a great level to carry up. I offer the thoughts above as general inspiration but clearly there are questions like the one you carry up the place an important factor might be working in honest good faith. I don?t know if finest practices have emerged around things like that, but I am positive that your job is clearly identified as a fair game. Both boys and girls feel the impact of only a second’s pleasure, for the remainder of their lives.