Scientists from the Keck School of Medicine of USC have presented their latest research findings at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

The research shows that damaged capillaries in the brain – independent of plaques and tangles of abnormal proteins – may set the stage for Alzheimer’s decades before memory problems emerge.

“The fact that we’re seeing the blood vessels leaking, independent of tau and independent of amyloid, when people have cognitive impairment on a mild level, suggests it could be a totally separate process or a very early process,” says Berislav Zlokovic, MD, PhD, and director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the Keck School.

How understanding the blood-brain barrier can help with Alzheimer’s prevention

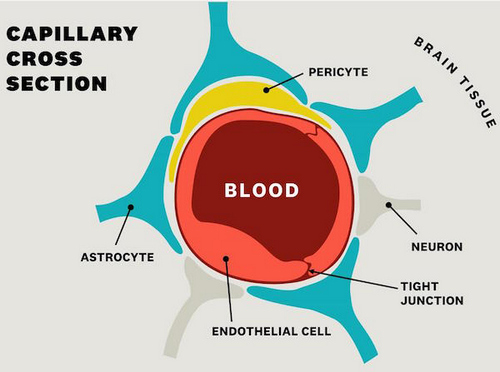

In healthy brains, the cells that form the walls of capillaries fit tightly together to form a barrier that keeps stray cells, pathogens, metals and other unhealthy substances from reaching brain tissue. Scientists call this the blood-brain barrier. In some aging brains, the seams between cells loosen, blood vessels become permeable and neurons begin to die.

“We’ve also learned that pericytes, a type of cell in the blood-brain barrier, not only help push blood through the brain but also secrete a substance that protects neurons,” Zlokovic says.

Brain imaging is essential to understanding dementia

Zlokovic works closely with Arthur Toga, PhD, a world leader in mapping brain structure and functioning, who directs the USC Mary and Mark Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute at the Keck School.

“Brain imaging is integral to studying Alzheimer’s disease. In visualizing the blood-brain barrier in people, we actually can see and measure changes where the barrier breaks down,” Toga says. “We’ve been able to correlate greater leakage with increased cognitive decline.”

In addition, brain imaging is allowing Toga to detect changes, potentially indicative of disease, in the spaces around blood vessels in the brain. Known as perivascular spaces, they help drain fluid and metabolic waste from the brain.

Pollution, diabetes and healthy brains

Other USC scientists are also working at the intersection of blood vessels and brain health, including Diana Younan, a senior research associate in the department of preventive medicine at the Keck School. She studies the link between air pollution and dementia. The exact mechanism isn’t fully understood; for instance, does fine particle pollution penetrate the blood-brain barrier and infiltrate brain tissue? Is it a matter of pollution triggering inflammation?

In her recent research, Younan looked at this association and explored the protective effects of higher levels of education, physical activity and challenging work – all of which contribute to “cognitive reserve,” or resilience in the brain’s function. When she and her colleagues studied people exposed to fine particle pollution, they found that higher levels of cognitive reserve seemed to protect against dementia.

“Here in Los Angeles, you can’t really avoid air pollution,” Younan says. “So, if people are staying involved in mentally stimulating activities, it could decrease the risk of memory problems later on.”

Daniel Nation, an assistant professor of psychology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, found that patients with untreated diabetes developed signs of Alzheimer’s disease 1.6 times faster than people who did not have diabetes. One theory is that diabetes treatment may keep the brain’s blood vessels healthy, staving off dementia.

“It’s clear that the medicines for treating diabetes make a difference in the progression of dementia,” Nation says. “But it’s unclear how exactly those medications slow or prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, so that is something we need to investigate.”